Memorial Day - My Uncle Niels

I wish I met my uncle Niels. We have the same birthday. May 23rd.

My uncle Niels was four years older than my dad. He was born in 1933 when birthdays of boys with blond hair and blue eyes like his were celebrated in Germany more than others.

My grandparents started a photo album on his birthday. "For our crown prince Niels," it says in handwritten Art Deco letters on the first page. "A document of his life, his travels, and his big adventures."

My uncle Niels was the first of three siblings. Five years after my dad, my aunt Swantje arrived. All of them had pearly skin, were blond and had blue eyes. My uncle Niels was the only one with a straight nose and straight short hair. They combed it Hitler-style across his head. In pictures, he wears short lederhosen, my dad sailor suits, and my aunt white dresses.

The pictures from his first two years show my uncle Niels looking curious at the photographer and the world around him, mostly wide beaches and happy-looking people posing in old-fashioned swimsuits. Later, there is a sense of distrust in his piercing eyes.

"Niels sold my pet-rabbit Mucki," my father told me when I was about 12. It was the first story I ever heard about my uncle who I did not even know existed. "I bred rabbits so we could have meat once in a while, but Mucki was my pet rabbit. He sat on my desk while I did my homework. I thought he escaped from his cage. Years later, neighbors told me that Niels had sold Mucki to the butcher."

I did not like my uncle Niels.

"Niels made up wild stories," my father told me. "People in town congratulated my mother for her son's achievements during the scholarship he received to visit communists in Moscow. My mother wondered where her son had been when she thought he was in school and the teacher thought he was in Russia."

I admired my uncle Niels.

"After the war, our parents sent Niels and me to beg for food at farms in the outskirts of our village. We walked more than 25 kilometers from dawn until after dusk," my father told me. "One day, all we got were five or six potatoes. Niels asked at the train station restaurant could they boil them for us. He told me that if I don't take any, he will eat them all. We had eaten only nettle and dandelion leaves the whole day. I gobbled one potato down. We came home empty-handed. I felt terrible. Still do."

I was confused about my uncle Niels.

"My parents could not handle him," my father told me. "He wrote coded postcards with only numbers on them. They sent him to an insane asylum where he stayed for a few months. Can you imagine what they did there to him? It was the late 40s."

I felt sorry for my uncle Niels.

"He ran away from home lots of times, was gone for weeks, even months. I saw him sometimes at night when my parents sent me into the forest to get wood for the stove," my father told me. "He was standing there in his flimsy jacket. He was freezing. He asked me could I bring him food?"

"Did you?"

"I tried, but we barely had any food to give away."

"Bullshit," my aunt Swantje said when I told her that story later. "There was chocolate and cans of liverwurst in the pantry. They were hiding it from us. Niels once broke the door open when those unfit parents had left us alone for three days and all those self-absorbed monsters put on the kitchen table was a loaf of dark bread, lard, and sugar. They never shared any of the good stuff with us."

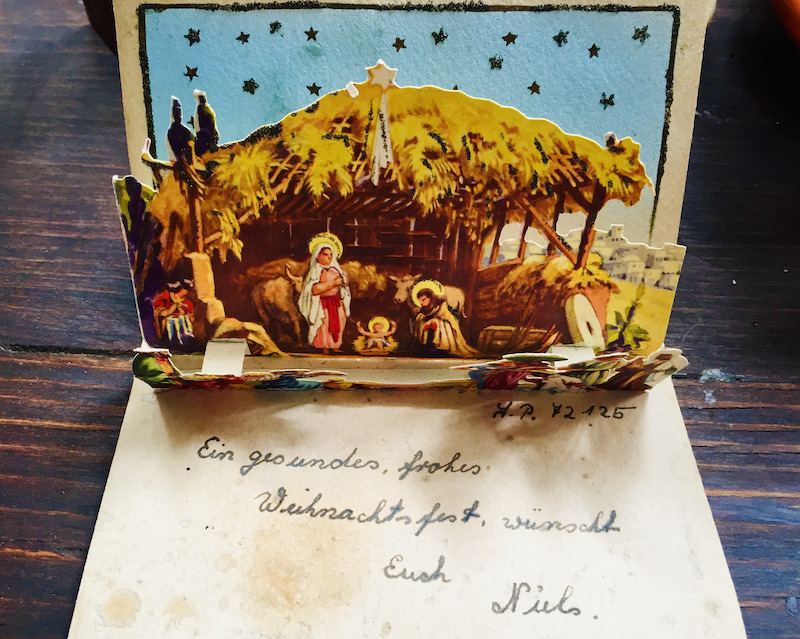

She gave me a postcard my uncle Niels had sent the family from Indochine for Christmas.

"heureux noel," it says on the front and when you open it, the nativity scene pops up: baby Jesus inside of a barn reaching for Maria and Joseph, all of them with haloes. In front of them: three kings plus noblemen in long robes kneeling to offer food and jewelry. The backdrop is a blue sky with golden and silver stars inside a frame that still leaves glitter on my hands.

"Wishing you a healthy, happy Christmas, from Niels," my uncle wrote on the card in impeccable longhand with a fountain pen.

"He sent this when he was 17," my aunt Swantje told me as tears rose in her eyes. "He had enlisted with the Foreign legion." She pulled a parchment-thin sheet of paper out of her desk's drawer. "He also wrote this letter from the front."

In it, my uncle Niels asks his parents to forgive him for everything he had done, the sorrow he had caused them, the disappointments, the lies, the embarrassment. He was begging them to take him back into their home once he would be able to return from the horrific scenes he witnessed every day. He signed: "Your wayward son".

I cried for my uncle Niels.

His parents were informed by the French government of my uncle Niels' honorable death on the battlefield at the age of 19. They thanked my grandmother for the big sacrifice she made and said she could pick up monetary compensation for her loss.

"That heartless woman went to the French embassy in Berlin the next day," my aunt told me. "She picked up that money and bought herself a pair of shoes."

I wish I met my uncle Niels and heard him tell his story.

please send your comments to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.